Anatomy of Windows Hello World program

07 Jun 2020Windows programming is in state of constant change since the introduction of Win32 api - whether it is move to .NET, again to WPF, introduction of Modern Apps which then got changed to UWP and now finally Project Reunion. One thing that hasn’t changed at all in this is how to write a hello world program in Windows. It has remained the same since 1995 when Windows 95 was released. However, a lot has changed internally. Windows does a lot of work under the hood to make sure the simple hello world continues to work even after 25 years and large scale OS changes. This blog attempts to go deeper into the hello world to showcase the rich technical background of windows hello world with a bit of history.

Why modern windows api are still called Win32 ?

Win32 api are the system level api for programming Windows at the lowest level. When Windows transitioned to 32-bits system with Windows 95, they wanted a way to distinguish these new 32-bit apis from existing windows api which were 16-bit only. That’s how the name Win32 was chosen for these new apis. Windows 95 was a mega hit and the lot of developers started using those apis to develop for Windows. More those api became popular, it became harder and harder to rename them. Changing to Win64 for 64-bit Windows or just Windows Api would have caused a whole lot more confusion and change of documents to remove 32 from the name. The name Win32 got stuck. Every Windows api is now Win32, whether it is 32-bit, 64-bit or any future foo-quantum-bit.

Hello World

The hello world code for Win32 has largely unchanged since its inception except when the infamous 3 pages long hello world program got replaced with a shorter version because it was intimidating to beginners. This anatomy is not of that infamous code but the successor since Win95 days which is decent sized and captures a lot of Windows functionality in itself. Let’s start by comparing this hello world with its console counterpart.

Console hello world

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::cout << "Hello World!\n";

}

That is pretty straight-forward. You have the IO header, entry point is main() and it calls cout in std namespace which prints hello world. Compare it to Win32 hello world. This code is directly from official MSDN Win32 hello world tutorial series presented unchanged.

Windows hello world

#ifndef UNICODE

#define UNICODE

#endif

#include <windows.h>

LRESULT CALLBACK WindowProc(HWND hwnd, UINT uMsg, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam);

int WINAPI wWinMain(HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE, PWSTR pCmdLine, int nCmdShow)

{

// Register the window class.

const wchar_t CLASS_NAME[] = L"Sample Window Class";

WNDCLASS wc = { };

wc.lpfnWndProc = WindowProc;

wc.hInstance = hInstance;

wc.lpszClassName = CLASS_NAME;

RegisterClass(&wc);

// Create the window.

HWND hwnd = CreateWindowEx(

0, // Optional window styles.

CLASS_NAME, // Window class

L"Learn to Program Windows", // Window text

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW, // Window style

// Size and position

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL, // Parent window

NULL, // Menu

hInstance, // Instance handle

NULL // Additional application data

);

if (hwnd == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

ShowWindow(hwnd, nCmdShow);

// Run the message loop.

MSG msg = { };

while (GetMessage(&msg, NULL, 0, 0))

{

TranslateMessage(&msg);

DispatchMessage(&msg);

}

return 0;

}

LRESULT CALLBACK WindowProc(HWND hwnd, UINT uMsg, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam)

{

switch (uMsg)

{

case WM_DESTROY:

PostQuitMessage(0);

return 0;

case WM_PAINT:

{

PAINTSTRUCT ps;

HDC hdc = BeginPaint(hwnd, &ps);

FillRect(hdc, &ps.rcPaint, (HBRUSH) (COLOR_WINDOW+1));

EndPaint(hwnd, &ps);

}

return 0;

}

return DefWindowProc(hwnd, uMsg, wParam, lParam);

}

On first glance, this looks way bigger and unnecessarily complicated. But it is showcasing a lot of functionalities for creating a GUI windows application. It launches a typical rectangular UI window filled with a background color. It has a functional UI, proper keyboard and mouse support and even event processing. Unlike other hello world programs for other platforms which are of little use outside of tutorials and first programs, this hello world is the foundation of any Win32 giant codebase out there. It teaches you all the basic things needed to program on Windows. Whether it is Photoshop or Firefox for Windows, they will have this piece of code somewhere in their giant codebases.

Now that, it is out of the way, let’s follow this code block by block.

Anatomy

#ifndef UNICODE

#define UNICODE

#endif

#include <windows.h>

Over the years, Windows programming has undergone large changes, like move from 16-bit to 32-bit api in Win95, move to NT kernel with XP and later changes for Vista and Windows 8. Any app whether the one developed in 1995 or in 2008 which calls windows.h continues to work in the latest version of Windows (excellent backward compatibility). Windows.h and Win32 apis do a lot of heavy duty work to ensure that all these apps remain compatible even when they are all including the same header. For example, if you are developing a new app which uses a legacy component (from Windows 95 era referring to windows.h header files of that era ), it is possible that your new component and legacy component will consume the same windows.h (from latest Windows SDK) and yet, pick up the era-appropriate functions.

It is a catch-all header for most common windows system calls. Windows.h, a small file on its own, carries forward declaration for multiple headers. For this hello world code, the apis are in winuser.h and linked using user32.dll. For any other functionality, some other header might be needed. Windows.h makes it easy by acting as a “router” for all these headers. You only need to include windows.h header and you get all this functionality. As MSDN page mentions, you can carefully select a different or smaller subset of functionality by defining few global identifiers like UNICODE here which indicates to use unicode variant of specific apis, denoted by W. CreateFoo resolves to CreateFooW More here.

Main function

int WINAPI wWinMain(HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE, PWSTR pCmdLine, int nCmdShow)

{

// Register the window class.

const wchar_t CLASS_NAME[] = L"Sample Window Class";

WNDCLASS wc = { };

wc.lpfnWndProc = WindowProc;

wc.hInstance = hInstance;

wc.lpszClassName = CLASS_NAME;

RegisterClass(&wc);

// Create the window.

HWND hwnd = CreateWindowEx(

0, // Optional window styles.

CLASS_NAME, // Window class

L"Learn to Program Windows", // Window text

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW, // Window style

// Size and position

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL, // Parent window

NULL, // Menu

hInstance, // Instance handle

NULL // Additional application data

);

if (hwnd == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

ShowWindow(hwnd, nCmdShow);

// Run the message loop.

MSG msg = { };

while (GetMessage(&msg, NULL, 0, 0))

{

TranslateMessage(&msg);

DispatchMessage(&msg);

}

return 0;

}

It is the entry point to the program. Win32 allows for 4 different entrypoints to choose from, if needed, using /entry linker option. On a quick glance, there are a lot of 0s and NULLs passed as arguments in functions. Many of these functions have existed since the inception of Win32 apis and have changed in their behavior. Thus, many of the arguments no longer have any effect and are left for compatibility sake. These arguments are always NULL or 0. For the rest of the arguments, flags can be combined with logical OR |.

The code uses a now outdated hungarian notation for variable naming where type of variable is prefixed before the name. Variable

bvalueindicates that it is a variable of type bool. MSDN provides a handy guide to read and understand variable names with these notations.lpszinlpszClassNamestands for long pointer (historically, a 16-bit pointer but a normal 32-bit/64-bit pointer in modern times) to string (ending in /0).lpfninlpfnWndProcstands for function pointer. Microsoft advises against using hungarian notation for modern Windows programming as it adds very little value and yet makes the code much harder to read. Joel On Software also has a good article on it.

Another interesting artifact of the past are wParam and lParam parameters. Before Win95, Windows was 16-bit OS. wParam was WORD param which was 16-bit and lparam was LONG param which was 32-bit. With Win95,Windows moved to 32-bit era and both WORD and LONG are now 32-bit (or 64-bit based on arch) so there is no difference between wParam and lParam.

HINSTANCE is another once of these - handle to an instance. This blogpost by Raymond Chen does a good job of explaining the reasoning behind it.

Window of Windows - Hwnd (pronounced as H-wind)

What is an Hwnd ?

“Obviously, windows are central to Windows. They are so important that they named the operating system after them.” - Official MSDN quote

A window is a rectangular area on the screen that receives user input and displays output in the form of text and graphics. In Win32 programming convention, a window is referenced by HWND - handle to a window. A handle is a numerical value associated with that window. In the kernel, an object is created for every window with an unique id. If a window is a person, hwnd is its name.

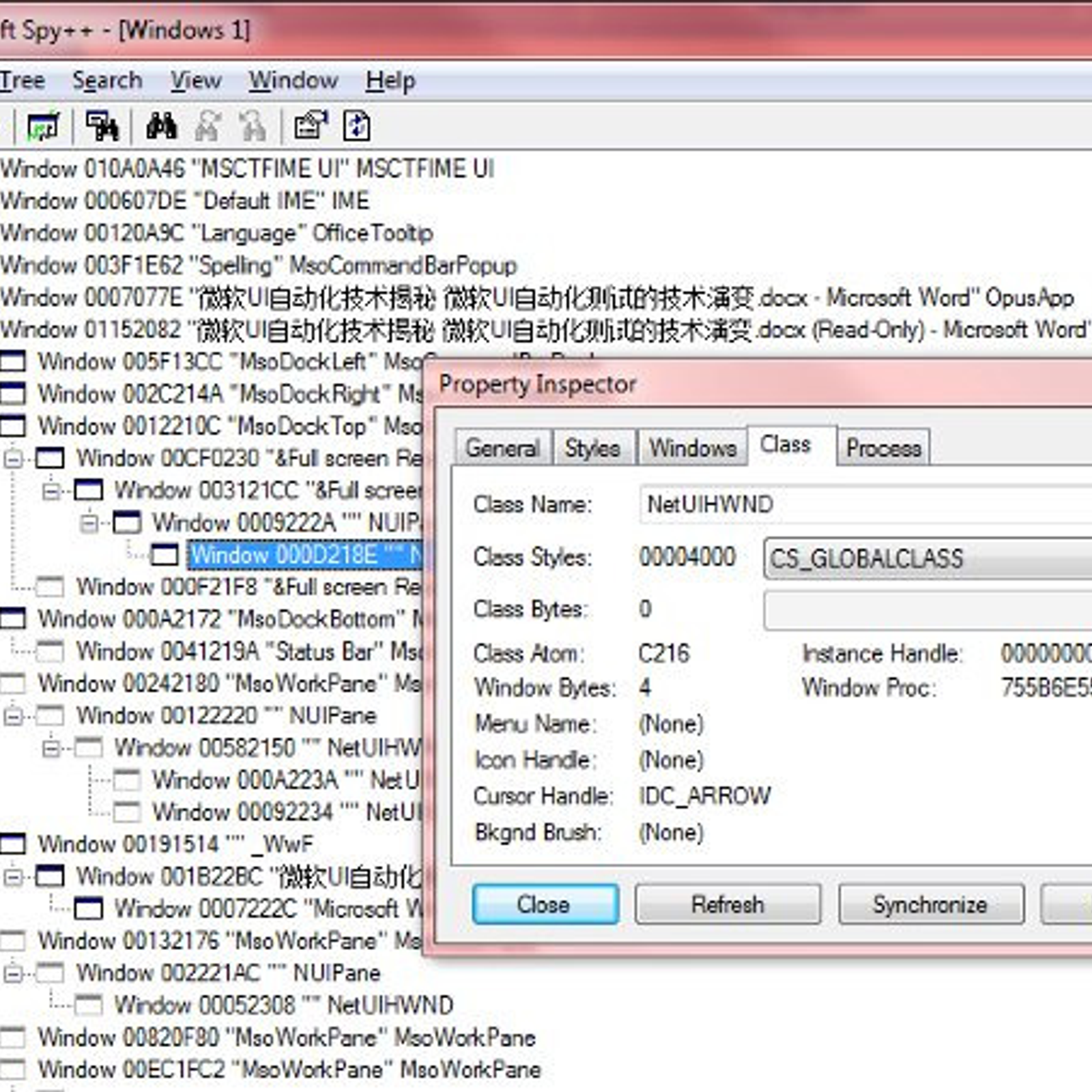

Everything is an HWND

In a true spirit of the movie Inception, every UI element in a typical hwnd is a hwnd itself (think recursions). This is achieved using child windows/owned windows. This leads to a lot of HWNDs in a moderately complex app.

, bundled with Visual Studio, is a good tool to visualize that.

Modern Windows HWNDs are hardware accelerated i.e. take help of graphics pipelines like Direct2D to draw pixels faster, using a GPU. Desktop Window Manager (DWM) handles drawing pixels on modern Windows.

Hwnd registration and window messaging system are the few pieces of code here which are reminiscent of very 80s Object Oriented (OO) design. Microsoft was on-board OO train very early on, even when it was not totally accepted by the industry. It was when Microsoft had been using only C for programming Windows. OO in C required a lot of weird design choices in Windows and because of backward compatibility, a lot of that design has stayed to this day.

Register the window class with OS

// Register the window class.

const wchar_t CLASS_NAME[] = L"Sample Window Class";

WNDCLASS wc = { };

wc.lpfnWndProc = WindowProc;

wc.hInstance = hInstance;

wc.lpszClassName = CLASS_NAME;

RegisterClass(&wc);

Windows has a weird way of doing inheritance. You will have to register your newly created hwnd object with OS for it to start communicating with it.

Create the Window

// Create the window.

HWND hwnd = CreateWindowEx(

0, // Optional window styles.

CLASS_NAME, // Window class

L"Learn to Program Windows", // Window text

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW, // Window style

// Size and position

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL, // Parent window

NULL, // Menu

hInstance, // Instance handle

NULL // Additional application data

);

if (hwnd == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

This code creates the HWND. We provide the window classes (we just registered) to be associated with this hwnd. Window creation api is very rich and can create 100s windows with different configurations and behaviors. One good example is creation of child windows. Since everything is a window. A button within a UI window is a child to that hwnd. That means the parent window can handle processing of messages for that child window. This kind of hierarchy is extremely useful. It is an implementation of inheritance concept from the OO paradigm. In this way, you can add a new window as child window of parent window and you don’t have to write any additional code for its basic operations like resize, maximize, close etc.

Show the window

ShowWindow(hwnd, nCmdShow);

Unsurprisingly, it shows the window on the screen. What is the point of explicitly calling show window ? There are many cases where a window is not shown directly. It can be created with the above command and updated using UpdateWindow and when ready, shown to the screen. There is also AnimateWindow for doing 90s PPT slide like transition animations which nobody should use in modern day and age.

Windows messaging system

Windows messaging system is a event-driven system achieved using polymorphism. The OS communicates to the program by passing messages and it will call a special function in your program to give you an option to deal with those messages. These messages can be keyboard, mouse, touch events generated on interacting with your program, or OS created events like when your program is minimized, maximized or closed. For this message passing model, Windows creates a single message queue for a thread which handles all the messages for HWNDs created on that thread.

Message loop

// Run the message loop.

MSG msg = { };

while (GetMessage(&msg, NULL, 0, 0))

{

TranslateMessage(&msg);

DispatchMessage(&msg);

}

Message loop code is what is responsible for filing up this message queue. There has to be only one message loop per thread. This message queue is hidden and not accessible by your code. It is handled entirely by the OS. All your code can do is to remove the topmost message from this queue using GetMessage() api call. This message is then translated for keyboard input so that it can handle shortcut keys and do other keyboard input processing (Read more here on TranslateMessage). After that, it is dispatched to the handler function WndProc (discussed below). GetMessage is a blocking function so it will wait if the loop is empty. But this doesn’t mean your UI will be unresponsive. An alternative to that is PeekMessage function which can peek and tell if there is a message on top of the queue. Since it won’t block, it is good for certain scenarios to do a “Peek” before a “Get”.

WndProc - the most important function in your code

LRESULT CALLBACK WindowProc(HWND hwnd, UINT uMsg, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam)

{

switch (uMsg)

{

case WM_DESTROY:

PostQuitMessage(0);

return 0;

case WM_PAINT:

{

PAINTSTRUCT ps;

HDC hdc = BeginPaint(hwnd, &ps);

FillRect(hdc, &ps.rcPaint, (HBRUSH) (COLOR_WINDOW+1));

EndPaint(hwnd, &ps);

}

return 0;

}

return DefWindowProc(hwnd, uMsg, wParam, lParam);

}

WndProc is the special function which has to be present in every Win32 program code, either directly or indirectly. It is the function which Windows OS calls whenever it has to communicate anything with your running code.

It usually has a giant switch statement for handling window messages like WM_DESTROY (what to do when a user clicks on the small x on the top-right of the window). It can choose to ignore it and it won’t close the window. Thankfully, there are other ways to close a window. This shows the level of control and flexibility Windows OS provides to developers which can be beneficial but can also be misused and the recent Windows programming model has evolved to counter that.

PostQuitMessage adds a WM_QUIT message to the message queue which causes GetMessage() to false, exiting the loop and exiting the program.

Your program doesn’t have to handle all the messages. It can handle a few special messages of interest and then call DefWindowProc - OS provided default handler to deal with the rest. WndProc can choose to handle messages for all windows in a thread or it can defer them to respective WndProc to handle. See Subclassing as example of dynamic polymorphism to achieve that.

Painting the window

The code within case WM_PAINT is the boilerplate code for drawing anything in a window. Windows Graphics Driver Interface (GDI) is immediate mode (link to it). A lot of newer UI libraries like WPF and WinUI are retained mode GUI frameworks because of memory and performance reasons. MSDN’s Painting the Window - Win32 apps does a very good job of explaining this code.

Compilation

MSVC is the compiler of choice. It can be compiled with Visual Studio or in terminal using msbuild. It needs kernel32.dll, user32.dll, gdi32.dll and /SUBSYSTEM:WINDOWS. Yes, the concept of subsystem has existed since start of Windows NT (because Windows was supposed to run OS/2 as subsystem which didn’t happen). That was helpful when Windows introduced Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) 30+ years later.

Ending notes

Thank you for reaching this far. The idea of this post came while I started learning Win32 apis for my work. MSDN does a good job of explaining the api but outside of that, a very little number of articles and blogs exist. This article aims to improve on that.

If you find any mistakes on the blog or have any other suggestions, let me know on twitter.